Analysis: The Legal Status of Liquid Staked Tokens: Security or Commodity? - Part 1

The legal status of cryptocurrency has prompted a heated

dispute between the crypto community and those who are ambivalent to the

cryptocurrency market. A recent development within the cryptocurrency ecosystem

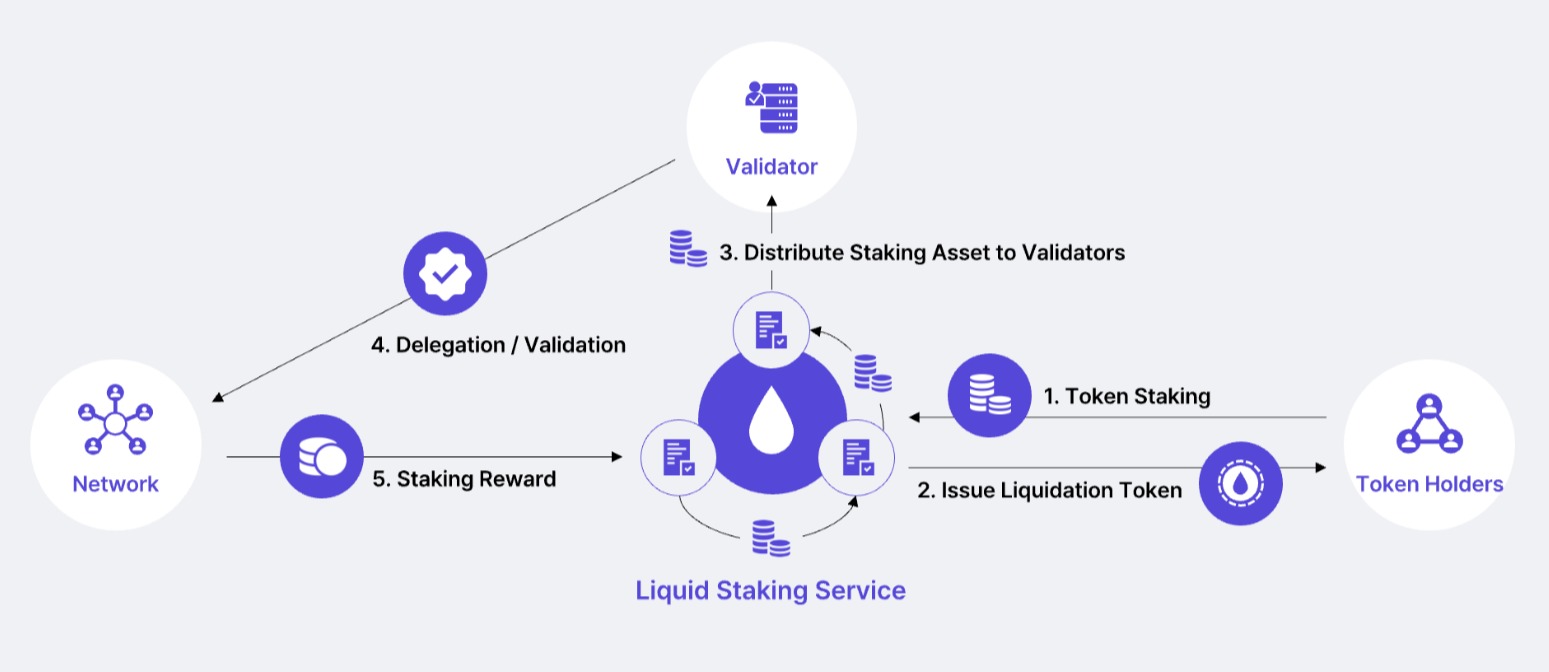

has been the introduction of Liquid Staked Tokens. LST is a category of

cryptocurrency that symbolises a user's ownership stake in a blockchain network

that uses proof-of-stake (PoS). Users can "stake" their tokens in

order to participate in network validation and gain rewards with PoS. Staking,

on the other hand, often requires users to lock up their tokens for a period of

time, limiting their liquidity and ability to use them for other purposes. LSTs

seek to address this issue by enabling users to trade staked tokens on

secondary markets while still earning staking benefits. The underlying staked

tokens are maintained in a smart contract, and LSTs can be redeemed at any time

for the staked tokens. The main cause of legal controversy with respect to

LST’s are whether a LST ought to be classified as a security or a commodity

under US law.

In order to gain a better insight into the issue of

classification let us first delve into the context of the situation in status

quo. Recent incidents have shown that the US Securities and Exchange Commission

(SEC) is actively monitoring cryptocurrency-related activity. For example,

Kraken was charged by the SEC for "failing to register the offer and sale

of their crypto-asset staking-as-a-service programme" and was forced to

discontinue the service in the United States, settling for $3 million in

February 2023. Similarly, in March 2023, the SEC sent a Wells notice to

Coinbase for parts of its staking services and exchange's listing processes,

saying that their staking service was not registered and could be categorised

as a security.

Despite Coinbase's efforts to address these concerns by

filing a Petition for Rulemaking on "Proof-of-Stake" Blockchain

Staking Service, the SEC pursued them nonetheless. These occurrences suggest

that the SEC will consider any crypto-related activity, regardless of its

nature, to be a security that must be regulated through enforcement. Not all

staking services qualify as investment contracts. According to the "Howey

test" and underlying policy and regulatory considerations, core staking

services do not fit the legal definition of a securities offering. As a result,

they do not pose the hazards that federal securities laws are intended to

address. However, the classification of staking services is not consistent and

varies by case. Regrettably, the SEC considers all staking services and staking

receipt tokens, including LSTs, to be securities and subject to the Howey test.

The lack of clarity in securities regulation is purposeful, as it is written to

be wide and inclusive rather than exact.

In Forman v. United Housing Foundation, Inc., it was

established that Congress opted to define the market it sought to regulate in

broad terms (421 U.S. 837, 849, 95 S.Ct. 2051, 2059, 44 L.Ed.2d 621 (1975)).

The term "security," as defined in SEC v. W.J. Howey Co. (328 U.S.

293, 66 S.Ct. 1100, 1103, 90 L.Ed. 1244 (1946)), must be broad and general

enough to embrace the different types of instruments that fall under our

commercial world's common idea of a security. As a result, rather than attempting

to limit the Securities Acts' application through particular procedures,

Congress established a definition of "security" that was broad enough

to embrace nearly any thing that could be offered for investment reasons.The

SEC has the authority to interpret the Howey Test in order to support its claim

of security. Despite efforts by law firms and legal scholars to argue that

staking as a service and liquid staked tokens are not securities under the

Howey Test, the challenge is that security status can only be determined in

court. An investment contract is defined by the Howey Test as (1) an investment

of money; (2) in a joint venture; (3) with the expectation of rewards; and (4)

generated wholly from the efforts of others. While general staking services may

be easier to justify under this definition, LST and SAAS are more difficult.

We will now focus on two options: either attempt to traverse

the onerous process of registering as a security with the SEC, or investigate

the prospect of approaching the CFTC (Commodity Futures Trading Commission),

which will take longer but is still possible. Any cryptocurrency project that

issues tokens in a "securities offering" is required to register with

the SEC or comply with an exemption from registration under this framework.

Exemptions for private offerings issued only to "accredited

investors" or exclusively to non-U.S. individuals are typically relied on

by cryptocurrency ventures.

There exist four primary methods to register or qualify a

token offering that allows non-accredited investors under the Securities Act of

1933 (the "1933 Act"). These methods are as follows:

· Conducting a "mini-IPO" under Regulation A

through Form 1-A3.

· Engaging in a Regulation Crowdfunding offering by filing

Form C4.

· Executing a standard IPO by a domestic issuer via Form

S-1.

· Conducting an IPO by a foreign issuer on Form F-1.

To register or qualify an offering, the issuer must complete

out the relevant form and submit supporting papers to the SEC, including at

least two years' worth of financial records. The SEC will analyse the

submission and give written comments, as well as any necessary revisions to the

filed forms. The issuer may not offer the securities until all of the SEC's

comments have been addressed and the form has been deemed "effective"

or "qualified."

If a project meets specific asset and holder requirements,

and if the tokens are considered "equity" securities, it may be

required to register under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. This entails

submitting Form 10, which takes effect after 60 days. However, in order to

avoid cancellation, the SEC may request that certain comments be addressed.Six

projects were required to register their coins during the ICO boom, however

five of them are no longer active in the US or making reports to the SEC.

Furthermore, none of the six tokens have any market or utility value. Staking

service providers are currently unsuitable for the SEC's disclosure system,

which places an inordinate focus on Form S-1.

Most tokens are incompatible with the framework because the

existing disclosure structure implies an issuer-security connection that does

not exist in decentralised systems. Despite registration attempts, the SEC's

lack of a practical framework provided through rulemaking, exemptive relief,

advice, and industry participation has resulted in failed initiatives. Instead,

the SEC has chosen a highly public enforcement-based regulatory approach, which

has fueled a clear turf war with the CFTC over jurisdictional control of

Bitcoin. As a result, it may be more useful to focus on demonstrating that

Liquid Staked Tokens (LST) can be classed as commodities under the Commodity

Exchange Act (CEA) rather than securities under US securities law, and to

engage in a discourse with the CFTC about potential commodity compliance.

What Makes the CFTC a preferable option

The CFTC's recent lawsuit against Binance has clearly

established a legal precedent. If the CFTC's case is successful, registering

with them may become necessary. However, in comparison to the SEC, the CFTC is

known to be a more transparent regulator, and they can provide guidance and

best practises for fair trade based on their experience in related fields such

as foreign exchange. Although not everyone will be pleased with the

regulations, if cryptocurrencies such as BTC, ETH, LTC, and stablecoins are classified

as commodities under the CFTC's jurisdiction, interesting developments may

occur.

While regulation by enforcement is not ideal in general, the

CFTC is enforcing existing rules that are already on the record in this case.

The Kraken settlement is a wonderful example of how the CFTC accepted

regulatory ambiguity while refraining from applying punitive sanctions. As

indicated by the working groups formed by the CFTC, there may be space for

development if a project makes a good faith attempt to comply and is ready to

help influence policy.

Continued in Part 2

Comments

Post a Comment